Synopsis

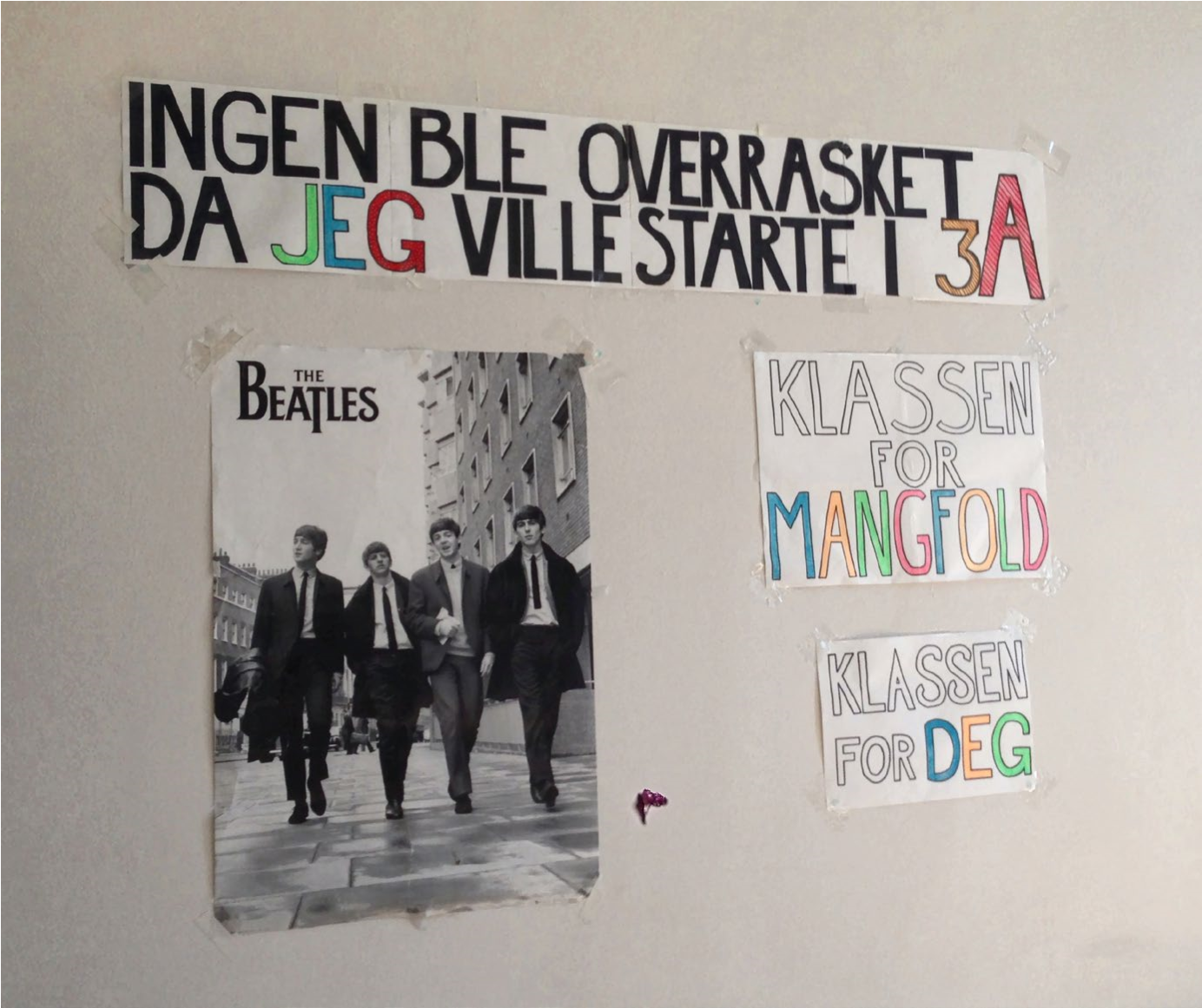

Hva er historiske eliteinstitusjoner, og hvordan er det å være en del av dem i det som betegnes som en særpreget egalitær kultur? Der hvor tidligere studier av eliter i Norge har gått kvantitativt til verks, og sett på sosial reproduksjon, tar denne avhandlingen en kvalitativ tilnærming og ser på kulturelle aspekter og konkrete erfaringer knyttet til å være en del av historiske eliteinstitusjoner. Halvorsen ser på eliteskoler og litteraturkritikk som eksempler på eliteinstitusjoner, det vil si institusjoner som har knyttet til seg visse kulturelle forestillinger om "elite". I studien finner han en rekke ulike måter aktører forholder seg til det å være del av historiske eliteinstitusjoner. Han finner blant annet at det å være del av en institusjon med elitetradisjoner ikke nødvendigvis innebærer at man interesserer seg for elitekultur eller kommer til å inneha en eliteposisjon selv; snarere er det slik at både eliteskole-elevene og litteraturkritikerne som er intervjuet strever med disse forestillingene og heller knytter seg til den egalitære tradisjonen. Slik sett argumenteres det i avhandlingen for at egalitære tradisjoner ikke er et slør for å skjule elitetilhørighet, men at forståelser av elite i Norge er sterkt preget av den egalitære tradisjonen.

This book is an edited version of my Ph.D. dissertation in sociology from 2020 with two newly written chapters (5 and 6). Many people should and could be thanked in this regard, but I will keep it short. First, thank you to everyone who participated in the interviews and shared their time and perspectives on different matters. Secondly, I would like to thank my advisors who have been of great inspiration: Kjetil Ansgar Jakobsen at Nord university, Håkon Larsen at OsloMet and Ron Eyerman at Yale University. I have had the good fortune of having people close to me outside of academia which I also include in my work and who provide me with help and motivation: Fredrik Wilhelmsen, Andrea Csaszni Rygh, and Torgeir Holljen Thon especially. I also must thank Anna Lund, Aksel Tjora and editor Balder Holm for their invaluable feedback on the dissertation and on how to turn it into a book. At last, I want to thank Nord university and the Faculty of Social Sciences for providing great circumstances for writing a dissertation. Nord university has also provided economic support for this open access publication. I hope it’s fun to read and that it might stimulate a sociological curiosity among the readers.

Oslo, 26.04.2024

Pål Csaszni Halvorsen

We come from different backgrounds and are born into life situations we cannot choose ourselves. This is true for elites as well as others.

This book explores cultural life in elite arenas – historical elite institutions – and how actors within these make sense of their positions. More specifically it looks critically at how privileges are handled and how these provide advantages to people, how certain symbolic assets become consecrated, and elevated above the rest. In other words, it is a study situated within the sociology of elites. It might be read as a study of inequality, but it is so only to the extent that inequality and equality are concepts central to meaning-making or legitimisation. In Norwegian society, studies of elites and inequality have received a lot of attention because of the allegedly egalitarian culture, and the political aims of social democratic governing politics (Lo & Dankertsen, 2023). Despite widespread support for politics of equality and a self-understanding as an equal society, there are nonetheless elite positions in Norwegian society, and these elites typically reside in specific elite arenas. This study positions its main questions in this crux between elite positions and egalitarian ideals.

This introductory chapter aims at providing the reader with a basic outline of the book and presents and familiarises the reader with the themes and concepts that are central to the research, such as “elite”, “egalitarianism”, and “institutions”. The first section of this chapter provides an introduction to studies of elites and elite culture and discusses the connection between literary criticism and upper secondary education as historical elite institutions. Following this, Chapter two will provide an account of how history, literature, and the social sciences[i] have described Norwegian culture as egalitarian, providing resources for meaning-making to which this study relates in multiple ways; notably these resources are available to and referred to by the interviewees. A third chapter on theoretical and conceptual approaches is then followed by a fourth chapter on the methodological approach, before the fifth chapter delves into the material and analyses. A conclusion with suggestions for further research closes the book.

1.1 Elites and elite culture in Norway

Elites have been studied in a variety of ways in Norway, for instance through surveys using a position method, or through a Bourdieusian analytical lens and multiple correspondence analyses. Yet, the research has not been sufficiently attentive to cultural aspects and life experiences. Instead, culture has been studied as a tool to maintain a social position, and not as the complex matter it is. First, it must be acknowledged that there is a plethora of ways of studying elites and elite culture as a phenomenon, depending on both theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches. To begin untangling the different ways it has been studied, we look at some core concepts. What is elite? And what does consecration entail?

Elites are often defined as people with “control over and access to a resource” (Khan, 2012, p. 362). Elites are assumed to have the power to set the terms through which tastes are assigned moral and social value (Holt, 1997, p. 95). This goes for taste in a variety of cultural products such as literature, music, food, as well as leisure activities and home decoration. In other words, it contains both the narrow and the broad definition of culture. When these values are assigned to different tastes, an effect is that cultural hierarchies are constructed, where the more valuable and less valuable tastes are ranked. Sometimes this is obvious, such as when certain authors get prestigious prizes, or when formal canons are made, such as the Danish government-initiated canon establishment in 2005–06, which resulted in a list of 108 artworks. Most often, however, this notion of a cultural hierarchy is not formalised. The vagueness of cultural hierarchies is a result of the subject of the ranking, namely culture, which has a long history of resisting categorisation and quantification. Booksellers as such are an interesting example since they have to negotiate the sacred literature and the profane economic aspects of books, and thus end up as “reluctant capitalists”, as Miller (2007) writes in her study; they work with literature and sell books at the same time. Publishing houses also have to deal with a similar dilemma on whether to publish highbrow fiction literature or supposed “literature that sells”, and in order to gain recognition as a serious publishing house they need to balance these two. This makes publishing houses internal redistributing organisations where the bestsellers finance the other books. In Norway the “book agreement” between the association of publishers and association of booksellers also ensures that competition is limited, and economic aspects are kept at a distance, given that all books are sold at a fixed price during the first year after publication.[ii]

A long tradition of sociologists has dealt with the question of taste, power, culture, art, and status – all the way from Georg Simmel’s investigation of Rembrandt in 1916 for instance, sociologists have questioned how it is that certain artists and certain works gain status and become objects that function as resources in society. Other artists worthy of similar attention have been Ludwig van Beethoven (DeNora, 1996), Vincent van Gogh (Heinich, 1997), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Elias, 1991), Gustave Flaubert (Bourdieu, 2000; Sartre, 1994) and Édouard Manet (Bourdieu, 2017), unsurprisingly all from the European, Western canon. Studies like these typically focus on one of four aspects: (1) a link between the specific aesthetics and the general social condition, (2) social conditions surrounding the artwork, (3) social relations connected to the reception, or (4) the construction of an artistic identity. This means that despite often bearing the name of one artist, these studies analyse either production, creation, or reception, which are the typical spheres of sociology of culture (Childress, 2017). Whether the products or knowledge about these artists or these works is called cultural capital, social resources, or connoisseurship is of a lesser importance in this study, which tries to take cultural hierarchies, even though they are vague, as a point of departure.

Schools also exist within cultural hierarchies, meaning that they have different status and are ranked. Faced with the choice of upper secondary education, one can often choose between schools with different specialisations and orientations, such as an economic school, an arts school and a sports school. There are also other aspects of importance to the placing of schools in cultural hierarchies, such as location and how old it is, and what kind of history it has. Together they designate some schools as elevated above the rest; they become elite schools. Elite schools, in turn, have the education of the elite as their goal. Attending elite schools then becomes partaking in consecrating activity.

This project deals with two institutions in Norway, literary criticism and elite schools, and their consecrating roles. In particular, this project deals with elite school students and book reviewers within these institutions. To attend elite schools or be a part of the literary world, actors often need to be recognised as having the right to do so, in the form of mastering the social codes or having the necessary education. During recent decades there has been an ongoing discussion about what counts as cultural capital, given its relational definition. In addition, these questions have been central: is legitimate arts still a consequential social resource, and the questions about which products and how they ought to be consumed. For instance, humanistic studies found legitimate arts as an inconsequential social resource in the U.S. (Huyssen, 1986), while sociological studies found a change from snobbish taste patterns to omnivore taste patterns (Peterson & Kern, 1996; Friedman & Reeves, 2020), and from national orientation to international orientation. The “omnivore discussion” and postmodernism overthrew or reshuffled many academic discussions about taste, culture, and power. However, the cultural history of certain works seems firmly grounded. These are the consecrated works that are elevated above the rest, meaning that they are assigned a higher status and are attributed an aura of significant value. They enter the elite. Lizé (2016) defined consecration as characterised by two complementary features: “(a) it concerns a high accumulation of symbolic capital, and (b) it implies a distinction between a select group of cultural creators or artworks that are worthy of admiration and the much larger group that is not”. Želinský (2019, p. 4), however, provided an interesting elaboration of consecration by emphasising the sacred, which lies at the etymological root of the term. He provides a telling example to clarify his innovation: “People do not pay the £4 fee (MacDonald & Erheriene, 2015) to visit Karl Marx’s grave because he was recognised as a legitimate participant in nineteenth-century intellectual discourse. They do so because Marx remains a cultural phenomenon that has been sacralised by social movements, individuals, and political regimes”. Thus, consecration becomes more than legitimisation. In this study, consecration is defined as the act of making people or artworks more worthy than someone or something else. How are such elevated statuses achieved? How are cultural hierarchies constructed? And is this special in cultures assumed to be egalitarian, such as the Norwegian one?

Another central discussion for cultural capital regards new sources and platforms, and communication of cultural evaluations. Grant Blank (2007) pointed out how expanding sources of information make it necessary for people to increasingly rely on the evaluation of others, through platforms like TripAdvisor, Yelp, IMdB or Goodreads, for instance. Traditional cultural authorities have resided in print media, especially the newspapers, whereas tomorrow’s cultural authorities might be both multiple and in a wide range of media. The present has been named “a time where everyone’s a critic” and “peak criticism”. Does that mean that traditional cultural authorities are on the wane? If so, it might be because criticism seems like “a holdover from forms of cultural authority long abandoned”, as Hanrahan (2013, p. 74) suggested. This cultural authority is closely associated with the elite and eliteness, which has to be negotiated in everyday settings: “status boundaries are reproduced simply through expressing one’s tastes” (Holt, 1997, p. 102).

This project about historical elite institutions relates these discussions in the overarching concept of consecration; the fact that something is given a status over something else. Individuals, groups, and objects can all be consecrated, and the consecration can also be undertaken by individuals and groups. Often a committee decides who to award a prize to for instance, which in the end might lead to consecration, or which album should be named “album of the year”. However, this leads to a narrow understanding of consecration since the process often takes many years, split into different events (Wagner-Pacifici, 2017) and tests. In other words, a prize is one small contribution that may result in consecration. Consecration is a “process by which actors and objects are symbolically elevated to the sacred position within the community and embedded in its foundational narratives” (Želinský, 2019). To be awarded an “album of the year” prize alone is not enough, but neither is success in one’s own lifetime. Here, the interest lies in the actors and objects that become qualitatively different than legitimised ones, and thus distinguished from the competitive nature of regarding culture as capital.

Attending a school becomes a way of consecrating oneself through an institution, which then materialises in diplomas. Sociological accounts often downplay the tests and events of elite schooling, for instance by pointing out the high degree of elite reproduction that occurs through these institutions (Bourdieu, 1996). In other words, what is most important is to attend them and not what you do there. This resonates with studies of general reproduction highlighting the importance of economic inheritance over wages (Hansen & Wiborg, 2019). The claim is that elite schools will provide their students with the necessary resources to achieve and maintain elite status no matter what effectively. The sociological studies can be read as a way of profaning the sacred elite schools, which often work as symbols for something more than themselves, making what is special about them rather mundane and predictable. This echoes the sociological studies of supposed “geniuses”, for example, the artists mentioned, where the idea of a genius is posed as an ideology and a myth instead of the historical fact it allegedly is treated as (DeNora, 1996 for example). In this scholarly tradition, sociology is conceived as a way of pointing out how common-sense understandings often are “mere illusions”. This project aims at something else, which is to try to understand why people believe in genius, or in elite schooling, and how people make sense of these in an everyday setting.

1.2 National consecration

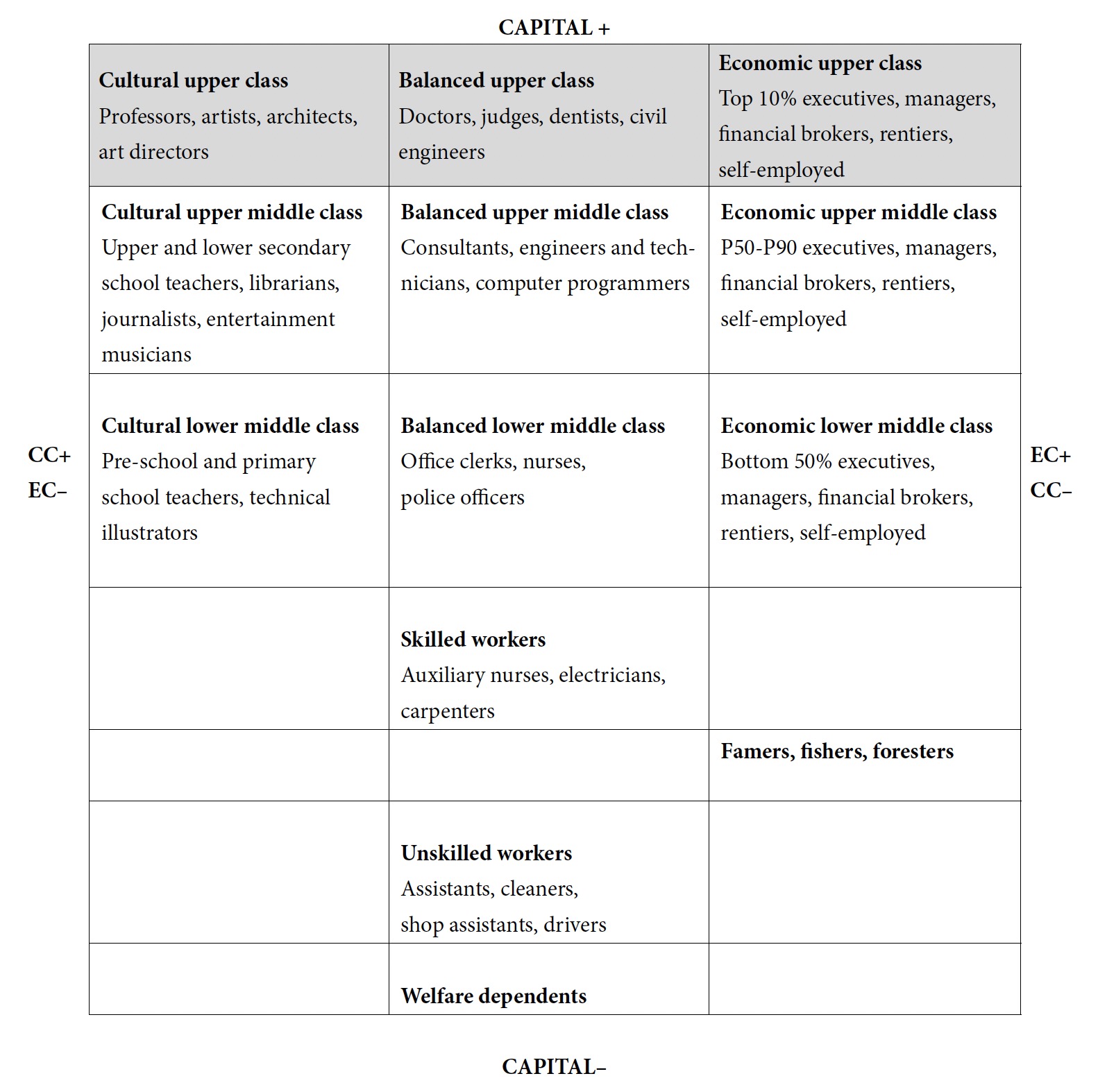

Sociologists disagree profoundly on the power of cultural knowledge in Norwegian society. There are two strands of research that have done extensive work on taste and class; the first in a Bourdieusian vein (Flemmen, 2013; Hansen et al., 2014; Hjellbrekke & Prieur, 2018; Jarness, 2013, 2015, 2017; Ljunggren, 2016, 2017; Prieur & Savage, 2013; Prieur, Rosenlund, & Schøtt-Larsen, 2008, 2015; Rosenlund, 1996, 2017); the second in the vein of French pragmatic “sociology of critique” and inspired by Michèle Lamont’s studies (Sakslind & Skarpenes, 2014; Sakslind, Skarpenes, & Hestholm, 2018; Skarpenes & Hestholm, 2015; Skarpenes & Sakslind, 2010, 2019). The former sociologists conceive culture as capital that can be exchanged into social success and benefits, while the latter poses that the Norwegian social democracy fosters a democratic culture, where preferences are “played down”, and in turn, makes the exchangeability of cultural capital into power particularly weak. This Norwegian downplaying of difference is coined by the French comparative sociologist Jean-Pascal Daloz as “conspicuous modesty”.

Historically, Norwegian culture is heavily influenced by literature and authors from the national romantic period when the Norwegian nation state was consolidated. It was named a “poetocracy” (Sars, 1913). Notable and important authors from Norwegian history are playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906), and Nobel laureates Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832–1910), Knut Hamsun (1859–1952) and Sigrid Undset (1882–1949), as well as the poet Henrik Wergeland (1808–1845). Literature was the most nationally oriented and politically most important art form, as well as a common cultural expression for national belonging and self-understanding (Slaatta, 2018, p. 54). Today, however, literature is only one of many forms of cultural production and interacts only to a small degree with other technologies than books. Norway has an extensive cultural policy, which provides good conditions for fiction literature, through what I would call “the sacred square of cultural policy”. This consists of: (1) public libraries, (2) the aforementioned “book agreement” between the association of publishers and the association of book sellers, (3) the standard contract between publishers and authors, and (4) the “innkjøpsordningen” [The Purchasing Program] of Norway’s Art Council. “Innkjøpsordningen” is a program where most of Norwegian contemporary fiction is bought by the Art Council and distributed to the libraries all around the country. The standard contract between publishers and authors is supposed to ensure that authors are decently paid, and under equal requirements. In addition, there is a historical predisposition for a reading culture with preference for print media, if we are to believe the claim of Hallin and Macini (2004), about the influence of the Protestant insistence of reading texts in religious practice. Hallin and Macini’s argument is that in Protestant cultures, as the Norwegian one, laymen were required to read the bible and therefore illiteracy decreased, and literacy increased drastically. Today 40 percent of Norwegians read over 10 books a year, and the general reading statistics are strong and stable. In this way, the literary culture in Norway played an important part in consolidating the nation state and is still visible as producing images of the nation through its high presence in the mandatory schooling system in the subject “Norwegian”. Colloquially, one could say that everybody that has gone through the school system has read the aforementioned authors.[iii]

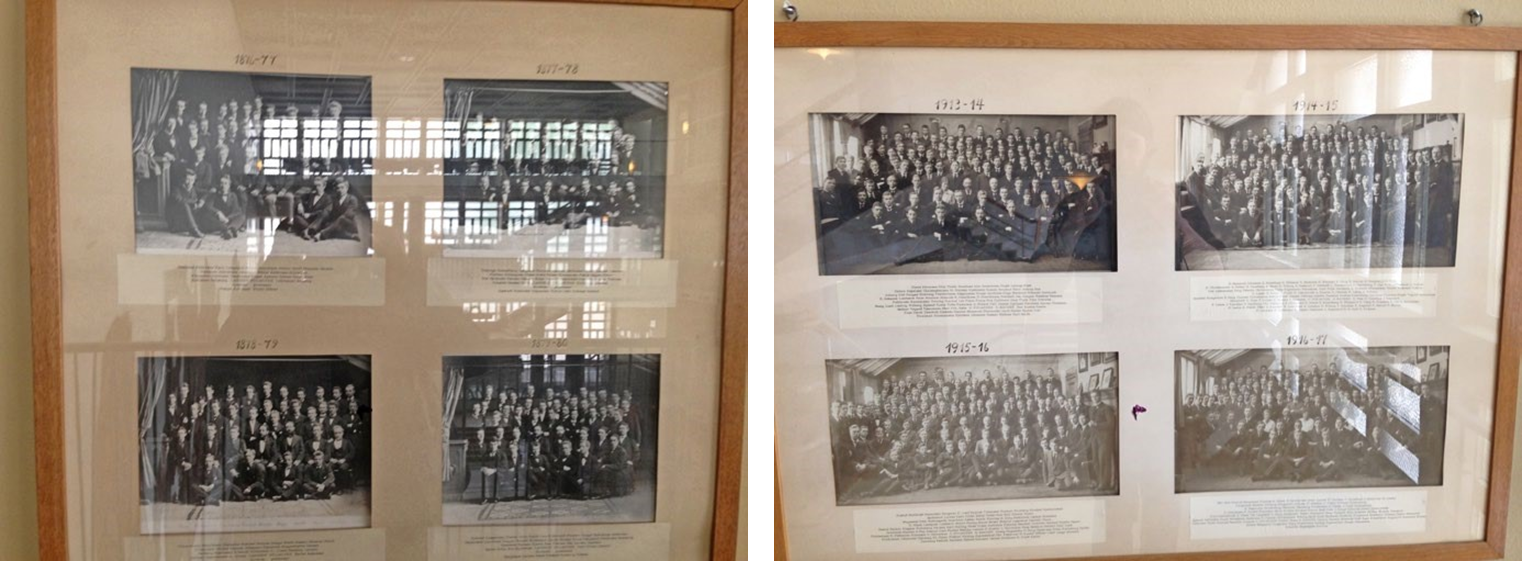

One of the largest collections of Henrik Wergeland’s writings is assembled at “the old library” at Schola Osloensis [Oslo Katedralskole / Oslo Cathedral School], one of Norway’s oldest high schools from 1153, given to them by the author himself as well as collected later. The library is run by an alumni organisation. It contains around 50,000 books; its oldest book is from 1488, making it one of the oldest and largest school collections in Scandinavia. The school is located next to the Cemetery of Our Saviour, where Wergeland is buried, as well as many other important figures in Norwegian history. This, I argue, provides the school with a certain aura. An aura which elevates it from other schools and makes it into a consecrated venue. The pupils at the school regularly use and work in the “new library”, but they have access and can tour the “old library” as well. How do circumstances like these affect the pupils? How aware are they of the history of their school, and how do they talk about it? Does it make them (consider themselves as) elite?

Norway’s oldest school specialising in commercial education from 1875; Oslo Commerce School [Oslo handelsgymnas] is also studied in this book, in addition to Schola Osloensis. They are both elite schools within the public system, which is free of charge. They are both located in the city centre of Oslo. However, Oslo Commerce School is closer to symbolically important institutions such as the royal castle, the parliament and the ministry of foreign affairs (as well as the former U. S. Embassy[iv]). During the Second World War, the school building was used as a command centre for the occupying German troops, which also built a bunker underneath it, which today is a museum. The history of the school is nonetheless proud, with numerous important alumni, such as ministers of both finance and foreign affairs.

The reason for combining elite schools and literary criticism in this study is that they are both important consecrating venues which highlight the role of cultural knowledge in Norway. By examining them closer we can get a better understanding of how hierarchies are negotiated, and maybe how they are constructed.

1.3 Historical elite institutions

The historical sociology occupied with institutions and legitimacy has its founder in Max Weber, and the conceptions of ideal types of legitimate rule: charismatic, traditional and legal-rational. This project is situated in the present, and rather than analysing trajectories or lifecycles, it regards history as a part of our present culture. The question of how change occurs through time has been a founding question for the discipline, as well as how people conceive and relate to it. Rather than aiming at a grand theory, or general explanation, this project digs down into two different, (on the surface quite different) institutions that are a significant part of the civil sphere. The institutions are the Norwegian high school system, exemplified through probably the most atypical schools within it, two elite schools, and literary criticism, exemplified through Norwegian book reviewing. These are approached through interviewing members of these institutions about their undertakings and perspectives on a wide range of issues. In some instances, historical knowledge can be regarded as a sort of social resource, available for those who have grown up in privileged circumstances and are working to reproduce their privileges. Nevertheless, this implies both a too rigid understanding of how changes occur through history and of individual autonomy (Alexander, 1995; Calhoun, 1993; Rancière, 2001). A cultural sociological approach like the one taken here is centred on the meaning-making processes and how meaning is constructed in society, which is irreducible to psychological or material factors, even though these also play a part. The approach is inspired by Alexander and Smith’s (2003) “strong program” and their insistence on the importance of analysing meaning in order to understand society. After all, sociology is the study of society and its parts, not just its parts (Adorno, 1999). The motivation for this project is therefore not to solve an empirical problem, or to explain a hitherto unexplained social phenomena, it is rather to explore and theoretically describe situations in order to understand them. However, as will be dealt with more thoroughly in Chapter 4, the relationship between explanations and descriptions are more complicated than indicated here, where the point is to highlight the motivation, not to describe the findings.

The book can be understood as an answer to the question of how historical elite institutions are negotiated in an egalitarian culture. The question could be approached in many different ways but given a quantity of good quantitative research on class, culture and stratification in Norway, a qualitative approach to unpack some of the experiences at the heart of these processes needed exploration. The choice of the cultural/literary sphere and the school is made in a typical Bourdieusian vein, so that it is possible to compare the findings with other research on elite distinction (Daloz, 2013), but mostly because they play an intertwined role in Norwegian culture (as I develop further in Chapter 2). There are two assumptions underlying the research question: 1) that the history of institutions can provide legitimacy, and 2) that the members have to maintain their status through everyday actions. One could assume the presence of anti-intellectualism that is often mobilised in cultural discussions in Norway makes the elite status into a status is hard to legitimise.

Nevertheless, with an abductive approach I have considered the project as explicitly “metaphysically pluralistic”, which is to say that no data, theory, or specific method is considered as having a privileged approach to social reality. Nevertheless, observations and use of categories are considered to always be theory-laden in this perspective, which makes for an interest in social actors’ own descriptions of what elite is, instead of the researcher’s categorisation of some as representatives of an “elite”. This also relates the approach taken here to the French pragmatic sociology of critique (Boltanski & Thevenot, 2006; Susen & Turner, 2014; Halvorsen, 2016a). As has been pointed out by several researchers, the interest in moving beyond a critical sociology to a sociology of critique can be seen as having more in common with Bourdieu than not (Dromi & Stabler, 2023; Kindley, 2016).

Following Alexander (2006), I claim that modernity consists of culture structures built around binaries, such as the Durkheimian sacred/profane. Consecration in this perspective means looking at how objects and/or actors become sacred, and regarded as something that transcends our earthly existence. It also becomes necessary to say something about its opposite activity: desecration. Desecration signifies the process of losing status, of becoming profane. In later years, desecration has gained attention when monuments and cultural heritage have been destroyed (Galchinsky, 2018; Zubrzycki, 2016).

This reminds us of the importance of not taking consecration for granted, as providing a stable position. Especially in our times, when people change objects at a rapid pace, the sacrality of objects seems to be very time limited, and this is often especially so for technological ones. So, the questions of how long objects maintain their status as sacred – and how they can lose this status – also become important. The sacrality of something has to be upheld through everyday actions, or else it will lose its status.

The recent years have seen an increase in studies of concentrated wealth on top (Farrell, 2020; Kantola & Kuusela, 2019; Khan, 2011; Kuusela, 2018; Schimpfössl, 2018; Sherman, 2017). Holmqvist’s (2017) ethnography from Djursholm, north of Stockholm in Sweden, which he labels as a “leadership community”, is also an example of this trend. He explicitly links this to the question of who or what provides consecration, which provides important insights into an elite arena. He writes about Djursholm as a specific place that consecrates its inhabitants, to a large degree because the inhabitants express a self-reinforcing myth about what it means to be an inhabitant in Djursholm. In our examples of education and book reviewing, the consecration is not happening in a specific geographical area, but it is rather the culture surrounding the institutions that provides the elevated status. Holmqvist shows how the place consecrates those living there, but he does not deal with the way in which a place could enact such a function. There is a clear problem of agency in his account, which in this project is dealt with in focusing on the acts where consecration is created. For example, Holmqvist writes a lot about the schooling in the area based on interviews with the parents, and people working at the school in very many different positions, but almost nothing with the students. This makes his account lack the aspect of agency in consecration, namely the aspect of those being consecrated, the ones “levelling up” and those who also have to maintain the high level. It makes his account overstate how consecration functions; in that it gives the impression that everybody is lifted up by this process. We know from different school statistics that this is not the case. There is almost always someone who drops out or fails in all school systems (Skarpenes & Nilsen, 2014).

These are the questions that have guided my research. How does the egalitarian culture of Norway manifest itself in accounts of assumed elites? How are cultural hierarchies legitimised in an egalitarian culture? What does it mean to be an elite member in an egalitarian culture? How is the elite culture of the institutions made meaningful by actors?

The following chapters will proceed like this: Chapter 2 presents the background for the research questions through the history of Norwegian selfperceptions and self-images, Chapter 3 presents the theoretical and conceptual framework for the project, Chapter 4 turns to the methodological considerations, and presents the research design and empirical material, Chapter 5 provides an introduction to the research at the elite schools and presents findings, whereas Chapter 6 contains an analysis of the critics’ description of the future need for criticism, and its role in society. Chapter 7 contains a discussion and conclusion.

[i] Sociology and social anthropology mostly.

[ii] This in contrast to more common book selling traditions following market initiatives and lowering the price of popular novels.

[iii] However, it is worth mentioning that this is a tradition currently undergoing a change, from focus on the canon to more focus on individual choice.

[iv] It was the U. S. Embassy during the interviews conducted there. The embassy moved to a new location in Oslo in the spring of 2017.

Discourses on equality and elite formation in Norway have been developed and shaped by social scientists, historians and authors over the centuries. Thus, the knowledge practices mobilised in this study are not only observers of, but also participants, even agents in the social world that is studied. This chapter will outline how authors, historians, and sociologists have discoursed on equality and helped shape the self-understanding of the Norwegian public. The need for a chapter like this appeared as soon as different conceptions of equality and nationhood appeared in the material from the interviews.

The chapter serves multiple purposes. Firstly, it will offer historical information and review literature and debates that are important to this study, but that may be less known to an international audience. Secondly, the chapter will help situate the study in a certain intellectual context and help the critical reflection of both author and reader.

The approach is to read national literature, history, and sociology[i] as self-proclaimed expert discourses on equality, discourses that have played decisive roles in the construction of national identity centred on conceptualising Norway as being a uniquely egalitarian nation. Historians, authors, and sociologists claim to know, each in their own way and for their own reasons, who the Norwegians are, and they all have proclaimed that Norway is the land of exceptional equality. Authors know this because of their artistic sensibility and their intimate relationship to the “mother tongue”, historians because they know the sources and origins of the nation, and sociologists because they are able to see and muster the totality of social facts. It is worth noting that the connection between historiography and the nation-state and nationalism is not (solely) a matter of ideology or agenda, as Krause (2021, p. 43) pointed out, but has “mundane institutional and material vectors” (as well). The chapter will describe from a second order perspective how this construction of national exceptionalism has been going on from the founding of Norway as a modern nation state through the Constitution of 1814, up until contemporary sociological debates. In summary, they have established different traditions, constituting repertoires of references that are available to actors in making sense of Norwegianness.

National character, conceived as a fixed mental set, is a myth; but as Michael Walzer pointed out “the sharing of sensibilities and institutions among the members of a historical community is a fact of life” (Walzer, 1983, p. 28). National identities, as well as the role and standing of cultural professionals and intellectuals in a nation are shaped through the activities of scholars and artists and codified and institutionalised by the school system and through the cultural and political institutions of the state and civil society. When identity discourses are institutionalised in this manner, notably through the schools, that may endow them with surprising inertia. For the major European nations –notably France and Germany the cultural power houses of the 19th century – these processes have been examined in detail and comparatively by historical sociologists Fritz Ringer (1969, 1992), Jürgen Kocka (1990, 1995) and Christophe Charle (2015).

As in other countries, in the 19th and 20th century, Norwegian artists as well as social scientists, engaged in the interwoven and conflictual processes of democratisation and national identity formation. Authors, historians and social scientists were poets in the original Greek sense of the term in the sense that they created a certain register for national identity, which Norwegians consider uniquely Norwegian. It has been pointed out for example by Kocka (1995) as well as Hroch (1998), Anderson (1991), and Kuipers (2012) that though people tend to understand themselves as unique, national identities are remarkably similar. Modern nations see themselves in the light of the key positive values of modernity – equality, freedom and solidarity – as well as pride in cultural achievements, natural beauty and some degree of military prowess, and they claim to be deeply rooted in history. Arguing that equality is a national trait is not specifically Norwegian, but the general depiction nonetheless has a Norwegian version.

2.1 Inventing the nation

Europe was the birthplace of the nation-state at the end of the eighteenth century, and “took the lead in inventing (and propagating) nationhood and nationalism” (Brubaker, 1996, p. 1). The Enlightenment thought of the 18th century, notably the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), established equality as the key value of society, along with liberty and the sovereignty of the people. The American and French revolutions of the late 18th century and their corresponding constitutions put this into letter and practice. The Norwegian Constitution of 1814, parts of which remains valid today, established the same principles for Norway. The movement of 1814 was a dual or triple revolution, which established liberal constitutional government, abolished privileges and the nobility (formally only in 1821) and established an autonomous nation state linked to neighbouring Sweden only through the person of the king and a shared foreign policy. Throughout the 19th century nationalist energies were, however, ignited by the fact that Sweden was clearly the dominant partner in the loose union, controlling the joint foreign policy, with the king largely residing in Stockholm.

In Norway, as in other European countries, the 19th century was the great age of nation building. A nation is here understood as an imagined community, that is a socially constructed community imagined by people that consider themselves to be part of it (Anderson, 1991). In such an understanding, nations do not become substances and entities, but institutionalised forms, practical categories and events (Brubaker, 1996, p. 16, Hobsbawm & Ranger, 1983). According to Anderson, the imagined community of the nation takes place in connection with the development and generalisation of print culture in the 18th and 19th centuries, with journals and daily newspapers, publishing houses and compulsory schooling, a perspective which holds true for Norway.

Independent Norway began in 1814 as a civic nation on the French model, stressing formal civic and political rights. During the 19th century cultural nationalism of the Herderian model became more influential (Sørensen, 1998). Narratives of Norwegian nation state building often start with the members of Norske Selskab (“the Norwegian society”) in Copenhagen. In this developmentalist narrative, the beginnings of the Norwegian nation state started with their patriotism and cultural mobilisation, which came to fruition with the uprising in 1814 and the constitution of May 17th. The Norwegian Constitution of 1814 provided the senior civil servants, in Norwegian called embetsmenn, with central roles. It is described as a tightly knit status group, in Weberian terms. The lack of both nobility and a wealthy bourgeoisie with political authority in Norway, allowed a period of relatively meritocratic rules of academics. In many ways it was a rule of upper middle-class people. Schola Osloensis, which was established in 1153, became very influential in this period, providing the educated elites, the mandarins, with the perfect preparation for university. First, by providing priests and senior civil servants to the autocracy before 1814, and afterwards to the constitutional government. Contemporary historians, following Jens Arup Seip (1905–1992), called it embetsmannsstaten (1814–1884) – the civil servant state, or the mandarin state, a regime for nation building and modernisation from above, run by civil servants. The historian Peter Andreas Munch (1810–1864) and the poet Johan Sebastian Welhaven (1807–1873) were two of its central ideologists along with the jurist and economist Anton Martin Schweigaard (1808–1870). Munch and Welhaven idealised the farmer, thereby making themselves “invisible” as a ruling group. National romanticism was the ideology of embetsmannsstaten.

The modern parliamentarian breakthrough in 1884 took place as a revolt, in opposition to embetsmannsstaten. In contrast, the French democratic breakthrough in 1871 was at the same time a breakthrough for a meritocratic society based on education. In the 19th century the Royal Fredrik’s University in Christiania [Oslo] was the only institution of higher education in the country. The revolt against the ancien régime of the embetsmannsstat was therefore necessarily also a revolt against the university and against the academy style literature of Welhaven and his followers. From this point on there is a distinct connection in Norway between anti-intellectualism and democracy, and it has become something that academics and intellectuals have had to manoeuvre around from early on (Jakobsen, 2011).

Norwegian intellectuals of the 18th and 19th century drew models and arguments from the European intellectual discourse of the time, notably the populist discourse of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Johan Gottfried von

Herder (1744–1803), cherishing the authenticity and cultural vitality of peasant culture. Early in the beginning a discourse developed, which was sceptical of an imported general European culture, stigmatised as finkultur (Jakobsen, 1995, 1997). Originally developed as a form of national romanticism by authors and historians affiliated with the ruling embetsmenn of the urban centres, this populist ideology was soon turned against the mandarins by later liberal and socialist movements.

When the embetsmannsstat ended, opposition groups merged in the party Venstre [the Left], and introduced parliamentary government based on political parties. The opposition had been building all the way since the 1860s. The historian Ernst Sars (1835–1917) was a key ideologist, along with the author Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832–1910). The two idealised the oppositional activities of author Henrik Wergeland (1808–1845) in the 1830s and helped create a politically effective “Wergeland myth” and the concept of “poetocracy”, which I deal with in the next part on literature.

2.2 “Poetocracy”

“Poetocracy” seems to have originated as a pejorative and satirical term in the late 19th century. It was Johan Ernst Sars, however, who in 1902 turned the pun into a serious concept. It aimed at explaining the position and role of authors in Norway at a formative period in the 19th century and up until around 1900. He claimed that authors, in their cultural creativity, defined what Norwegian culture was, and had an enormous impact on public as well as political life. Not only did they impact decisions, but they actually made them through their implicit and explicit work. Sars wrote this in an article about Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s influence on Norwegian politics, as a digterpolitiker [a poet politician], but also used Henrik Wergeland as an example.

Wergeland is generally considered the finest Norwegian poet ever. By the time Sars wrote about Wergeland, he was already well on his way to be canonised as the poet of the nation, in a role similar to that of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller in Germany, Victor Hugo in French republicanism, or Adam Mickiewicz in Poland. Unlike the national romantics of the previous generation, Sars stressed the political radicalism of Wergeland, his role as one the leaders of the opposition to the dominance of embetsmennene. Wergeland, in short, was depicted by Sars as both the symbolic founding father of modern Norway, and of the patriotic Venstre-coalition of farmers and liberal townspeople who brought down the rule of the embetsmenn in 1884, making the Government accountable to the parliament. Wergeland edited Statsborgeren [The Citizen (of the State)], the leading opposition newspaper of the time, and he was active both in the student, farmer and working people organisations.

Wergeland was a tremendously prolific writer in all genres, notably poetry and drama, in addition to being a historian. Unable, due to his radicalism, to get any position in the Norwegian civil service, the king would eventually try to appease the situation by arranging him a post as national archivist (Storsveen, 2008). His father, Nicolai, was one of the writers of the Constitution of 1814, an eidsvollsmann, and patriotism and Rousseauian radicalism ran thick in his family. Kåre Lunden (1995) explicitly names Henrik Wergeland as one of the most influential thinkers in Norwegian historiography, amongst others due to his Norges Konsititions Historie [The History of the Norwegian Constitution] (1841–3), even though he was “hardly an empirically outstanding researcher”. He played an important part, together with Keyser and P.A. Munch, in shaping the Norwegian national narrative of the 19th century. Despite, or perhaps because, his notoriety with the authorities, and despite living a short life, he was something of a media celebrity, with a huge crowd following him to his grave when he died at age 37 in 1845. Wergeland wrote a huge number of letters and newspaper columns that have been the basis for several literary studies, and the largest collection of his writings is at the library of the high school he attended, namely Schola Osloensis. Sars named the period from 1830–1845 “the Wergeland period” and claimed that Wergeland personified what went on at the time (Fulsås, 1999, p. 254).

Whereas Wergeland represented the youthful and enthusiastic lust for a new national culture, Bjørnson represented the full-grown and responsible version, according to Sars. They both had a need to be agitators and public intellectuals as well as authors, but in a mutually reinforcing manner, where the different activities advanced each other. The most important for them was to “take hold of matters in life”. Understanding the farmers was of vital importance for them both if we are to believe Sars. The historian holds, however, that where Wergeland was an enthusiast who wrote for and about farmers, but never understood them, Bjørnson managed to paint “true and touching images of the Norwegians farmer’s inner life”. Wergeland and Bjørnson were also separate in their views on Scandinavianism, where Bjørnson in his youth was clearly in favour, while Wergeland was a Norwegian patriot and a cosmopolitan. In the 19th century, politicians had to deal with poets “and prophets” entering the political stage with their “fantasies and moralism”. Sars creates the impression of politics as an almost bureaucratic and grey chore, in need of external injection of fantasy and moral, which was what the authors provided. “Big targets are not achieved through small measures”, he writes polemically. In other words, we get the impression that authors could bring “big words” and great ideas to a political debate that lacked temperature.

The stride between Wergeland and Welhaven is well known in Norway, as it is a part of the curriculum for everyone in the Norwegian education system. Wergeland’s free and avantgarde poems are read with Welhaven’s bourgeoisie (“finkulturelle”) rhyme-based ones as a contrast, and in many ways, they are exactly that. They were contemporaries, and they explicitly disapproved of each other’s artistic visions. In many ways this can be read as an example of Bourdieu’s distinction between avant-garde culture and bourgeois culture, that is between preferences for the heavy and the light, left and right bank theatre, and so on. Welhaven constitutes the autonomous pole of the literary field, which was being created, whereas Wergeland pioneers the heteronomous. Welhaven and his circle, which was happy to let itself be known as “intelligensen” [the circle of intelligence], pioneered a new continental style of educated urban life, where both genders met in clubs or salons to drink wine or tea, converse and enjoy culture. Wergeland would often wear peasant clothing and indulged in the traditional drinking bouts of student life. Wergeland’s mix of avant-garde poetry, popular dress, bohemian lifestyle, social engagement, and patriotic fervour, and his claim to be authentic in defiance of conventions – his most famous poem is Mig selv [Myself]; it all came together and set a model, a habitus perhaps, on which the Norwegian field of literature has drawn ever since. Every pretender to a hegemonic position in the Norwegian field of literature is measured in light of “the Wergeland myth”. With the great influence of Wergeland’s model, and the limited influence of Welhaven’s, it may be that literature fits the Bourdieusian model less neatly in Norway than in some other European countries because of the prestige of heteronomous literature. The legacy of the poetocracy is literary avant-gardism in favour of equality and common culture (a similarity with the American literary canon, exemplified with Emerson and Hemingway for instance, whereas the French, German and English literature rests on altogether different conceptions of literature and culture). Norwegian literature might as such be an anomaly (Tavory & Timmermanns, 2011; Vassenden, 2018), in that heteronomous literature in many ways inhabits a higher position than theory would assume. However, the examples that do not neatly fit in with theory, provide an opportunity to theorise and discuss theorising in sociology. The position of Wergeland is connected to the close link between nationalism and liberalism in Norway, that enabled cultural expressions of societal matters and gave them a priority it lacked in some other countries. This is what Sars meant by “poetocracy”, which did not occur to such an extent in Denmark and Sweden because they were old, well-established nation states, where liberalism and nationalism were more distinct, according to Sars. On the other hand, Sars tended to overlook the less flattering aspects of the authors and reduced them to characters in his own storytelling.

As the section on historical accounts will show, there have been noteworthy elites in Norwegian history, and also in cultural life, but elitism, and culture that is not rooted in egalitarianism, has had a hard time getting accepted (Stenseth, 1993). In other words, it could be so that elitism, even when meritocratically grounded, has an especially weak position in Norway compared to other countries. Another cultural influence worth mentioning in this regard is the Haugianism, after the Norwegian lay priest Hans Nielsen Hauge, who won great popular support for a Norwegian version of the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism, while challenging the authority of the educated elites (Myhre, 2004, p. 129).

The concept “poetocracy” has become part of Norwegian self-conceptions. It has been expanded to include other central authors such as Henrik Ibsen and Alexander Kielland. They all wrote in a period often explained by the Danish literary historian Georg Brandes’ formulation of the objective of literature in society: “to set up problems for debate”. Central works from this period dealt with the role of bourgeoisie families, and public life – the break from a traditional period, towards a modern phase. Alexander Kielland wrote from the city of Stavanger about the challenges of merchants and ordinary folks. His novel Arbeidsfolk [Labourers] from 1881, is in many ways an articulation of standssamfunnet [The Society of Status Groups], where the different leaders of parts of the work organisations use the highest title when they refer to each other. By doing this they underline verticality, and rank. Another central novel by Kielland is Gift [Poison] about the teaching of Latin in school, which Kielland criticises. Also in this novel, we find a break with the traditional (Latin as a school subject), and an emphasis of modern society, where school is supposed to be more open. Ibsen wrote about women’s position in society in Et dukkehjem [A Doll’s House], the role of religious belief in Brand and the role of dissidents in political cultures in En folkefiende [An Enemy of the People], for instance. Jakobsen (2004) claimed that Ibsen raised the literary field in Norway to higher levels of autonomy, in an analogical manner to what Flaubert did in France, according to Bourdieu’s The Rules of Art. They self-objectivated themselves, using the literary tools at their disposal to capture various forces at play in the field of literature; thus, providing reflective autonomy in relation to those forces.

In 1970 “the poetocracy” was declared “dead”, by the young philosopher Gunnar Skirbekk. It should be borne in mind that he was a social philosopher, a follower of Jürgen Habermas and a self-proclaimed speaker for the social sciences. It was the death of important culturally radical authors, such as Sigurd Hoel, Helge Krog and Arnulf Øverland, that made him claim this. Allegedly, they were the last bearers of “the poetocracy”. Newly established social scientific disciplines, such as sociology and political science, were populated by people who took on the role previously held by the bearers of “the poetocracy”. In short, Skirbekk proclaimed that public intellectuals were more likely to come from this background than a literary one.

In 2004; Gunnar Skirbekk revisited his prognosis about the death of “the poetocracy”. He restated his views on fiction playing a vital role in Bildung and maintaining a political culture. Fiction “develops codes of meaning, self-conceptions and values [… it] teaches us to see ourselves and the others” (p. 438). He also reinstated the importance of literature in Norwegian history alongside the popular movements, “The discrete charm of the North”, as he calls it, but he ends on a concerned note. Not only is the poetocracy dead, but this time he is also concerned for the future of philosophy and social sciences which he considers differentiated and specialised, and no longer preoccupied with public culture.

2.3 National history – egalitarianism as a national narrative

The historians were pioneers for the critical study of elites in Norway, as well as contributors to the discourse on Norwegian identity. In this part, we will look closer on a couple of influential historians and their work. “Norwegian historical scholarship has primarily been a national historiography”, Hubbard, Myhre, Nordby and Sogner (1995, p. 6) pointed out and drew our attention to notable examples of Norwegian historians, such as Rudolf Keyser (1804–1864), Peter Andreas Munch (1810–1864), Ernst Sars (1835–1917) and Halvdan Koht (1873–1965). The first academic historian to frame a major narrative around the theme of Norway as an exceptionally egalitarian nation seems to have been Rudolf Keyser. Together with P.A. Munch, he was the leading exponent of what Danish historians with some sarcasm called “The Norwegian historical school” (a pun on the famous “German historical school”). Based on speculative philological and no archaeological evidence, Keyser and Munch claimed that Norwegians (and some of the Swedes) were a Norse group, who had wandered in from the North, while the Danes and southern Swedes descended from Germans. This is known as “the immigration theory”, constituting Norwegians as a unique people. This “theory” was soon to be accepted as truth in the Norwegian population, according to Dahl (1959, p. 51). Rudolf Keyser and P. A. Munch are understood as national romantics (Kjeldstadli, 1995). They explicitly connected Norwegian culture with values such as democracy and freedom and highlighted the foundation in the allodial right (“Odelsretten”) as a building block for Norway, providing freeholders with absolute authority in political meetings, the “ting”, and making farmers a unifying force in the history.

The historical interpretations by Keyser and Munch of Norwegian national development have strongly influenced public debate and self-perception (Dahl, 1995; Melve, 2010). Marte Mangset (2009, p. 424) argued that these formative decades not only formed the content of historical research, but also how Norwegian historians perceive themselves as disciplinary agents up until today. They were preoccupied with explaining how Norwegian culture and identity was formed, and doing so in a culture they themselves were a part of.

In his overview over Norwegian historiography and central actors, Lunden (1995) wrote: “All of these looked for the essential Norwegian history and Norwegian nationality among the farmers”. He dates Norwegian egalitarianism to the farmers’ “Storting” [parliament] of 1833 and 1836, and the 1837 law of on municipal councils. The main point is that the Norwegian society was not feudal as in Sweden and Denmark, and thus were more open and egalitarian. However, one can question this depiction of Sweden, which like Norway has a continuous tradition since the medieval ages of free, self-owning farmers with parliamentary representation, and which unlike Denmark and Norway, never turned into an autocracy (Bengtsson, 2019; Piketty, 2019), but this seems to be of lesser importance to Lunden. For Lunden, a fundamental trait of these early historians is an evolutionary perspective and a teleological conception of history as progressive towards the better. He dates it back to Henrik Wergeland’s writings: “[H]e developed the main lines in theories which later became more known through Ernst Sars” (Lunden, 1995, p. 33). The historical work laid the basis for the work of a national cultural revival, played out by Per Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, who gathered and wrote down popular fairy tales, Welhaven, Bjørnson and Ibsen, who wrote plays that thematised Norway and Norwegian identity, Johan Christian Dahl and Adolph Tidemann, who painted landscapes from around the country, its fjords and mountains, and Ole Bull, who composed music with elements from traditional cultures. This period (ca. 1840–1870) is known as the national romanticism (Dahl, 1959, p. 44), where international influences from Johann Gottfried von Herder, gave inspiration to develop their own national works rooted in Norwegian folk culture. Central was the search for culture among farmers and common people, and the high culture of earlier times in Norway was disapproved of, according to Lunden (1995, p. 37). As will be mentioned several times throughout this book, the period of national romanticism has been influential in creating a self-conception of the Norwegian society, where equality and sameness is central, and inequality and eliteness under-communicated. The reason for this is thought to be the need for proving a national identity to oneself, because of the Norwegian state and society’s weak position internationally at the time (Dahl, 1959, p. 44).

In addition to Herder, influences from Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich von Schelling are put forth by Kjeldstadli (1995) as important for the national romanticism, and he points out an affinity for ethnographic approaches. Despite being influenced by these international references, Kjeldstadli (1995, p. 55) claimed that they looked “upon theory as a necessary evil or even a nuisance”. Norwegian historiography was known for emphasising the craftsman’s ideology in favour of a more theoretical approach. Dahl (1959, p. 19) also pointed out that common European isms such as “romanticism”, “nationalism”, and “liberalism” also influenced different generations and schools of historians, but as “unreflexive and unobtrusive schemas of thought”. Kjeldstadli (1995) describes Sars as believing in a step-by-step progress towards freedom. Sars’ writings are described as having four traits: (1) evolutionism, (2) belief in progress, (3) idealism and (4) searching for explanatory laws. Dahl (1956) described Sars as a positivist. The inexplicitness of theory goes through other important historians as well, such as Halvard Koht, Edvard Bull Jr., Sverre Steen, Jens Arup Seip and Andreas Holmsen. Kjeldstadli nonetheless interprets their works in order to explain the theoretical underpinnings of their writings. There are differences, but mostly there is unity, a “quarrelsome unity” (Kjeldstadli, 1995, p. 52). The one that stands out is Ottar Dahl, who wrote the only purely theoretical work produced by any major Norwegian historian, a study on causation in historical research (Dahl, 1956). All the way up until the 1970s, Norwegian historiography have been considered evolution-optimistic, and one reason for this might be the long-standing Norwegian tradition of writing the nation’s history for the general reader in large works of many volumes to be found in every educated Norwegian home (Lindblad, 2010; Sejersted, 1995). Also, there is a great interest in local and regional history in Norway, providing work for many historians outside of the universities. In Sweden and Denmark, national history has not enjoyed the same popularity, and thus, history might have been academized to a greater degree.

Probably the most influential Norwegian national narrative has been written by Ernst Sars. He belonged to the what is called the Lysaker Circle, a neo-elitist group of liberal intellectuals who reframed and modernised the Norwegian self-image towards the end of the 19th century (Stenseth, 1993). For Sars, the relation between elites and democracy was dialectic. He described elites as drivers of history, that fulfilled their historical mission when the culture they created was democratised and the elites themselves absolved in the totality of the nation.

The industrial and capitalistic breakthrough towards the end of the 19th Century saw an increase in wealth, and the formation of an elite in Norway as well. The Oslo Commerce School was founded during this period, in 1875, providing at the time the highest commercial education in the country. Not long after, in 1889, a law was passed that claimed that all children had an equal right to elementary education (Folkeskoleloven [the Law of the Volksschule]), and with it the subject of “Norwegian” that solidly founded literature as important for all to read and learn. A democratic literary ideal was founded through the reading books of Nordahl Rolfsen, where everybody was supposed to read the same, and literature was supposed to make the pupils into “decent Norwegians” (Gujord & Vassenden, 2015, p. 285). This literary ideal in what later became known as the “One School for All” policy of Norway has persisted up until today, and at the same time at least some canonised texts have been central (Gujord & Vassenden, 2015).

Halvdan Koht is particularly interesting for being the first Norwegian historian influenced by Marx, in that he focused on divisions between classes in society. However, he read it into a question about integration, the different “classes” throughout history became integrated into the nation: first, the farmers in 1884, and then the workers in 1935, when the Labour movement came to power. He is considered a central ideologist of “Arbeiderpartiet” [The Worker’s Party], and from 1935 to 1940 he was Minister of Foreign Relations.

According to Myhre (1995, p. 227), the establishment of social history at the University of Oslo was a watershed. This was mostly due to the research project “The development of Norwegian society, circa 1860–1900”, which was a collective organised around Sivert Langholm. They produced four books, many articles, and over 50 master theses. They studied specific groups, instead of the nation, and used quantitative methods, hitherto uncommon.

In the second part of the 1970s, Knut Mykland edited a fifteen-volume history of Norway, which is considered the first example of social history in Norway. The use of social theory expanded, and “sociology was the main supplier” (Myhre, 1995, p. 225). Edvard Bull Jr. named the last one, the chapter on the 1970s, “The New Insecurity”. This signals a shift from the positive and general account of historians to a sensitivity towards the “invisible” in history. The projects were more specific than the general narratives of former historians, but they still had the modernisation of Norway as a contextual frame. Kjeldstadli and Olstad wrote about the transition from an estate society (standssamfunn, as in the Weberian “Stand”) to a modern class society.

The social historians, like the Norwegian sociologists at the time, took little interest in the study of elites and the educated middle classes. A critical perspective on elites was, however, offered in the very influential work of the historian Jens Arup Seip. Seip ostensibly continued the Rankean tradition of studying high level politics through the scrutiny of written sources. He did, however, give this venerable form of history writing a new twist by focusing on how political life in democracies systematically hides what according to Seip is really going on; the monopolisation of power by elites, and the struggle between and within elites. Seip conducted a critical analysis of Norwegian 19th Century elites in his study of embetsmannsstaten, and he also did so in a critical take on Norwegian social democracy (from 1945 onwards), which he named the “one party state”, pinpointing the tacit alliance of the labour party machine with technocratic and bureaucratic elites. Seip, in short, was the realist who deconstructed certain national mythologies that had hitherto been propagated by the profession of historian.

Despite introducing social issues, and providing, in the case of Seip and some of his followers a more realistic understanding on the nation and its politics, the historical accounts are still known to rely on the national level, with a focus on the characteristics of Norwegian society. Sejersted (1993) called this the Norwegian Sonderweg, where ever since 1814 the state fostered economic growth on behalf of the citizens, compensating for the lack of a capitalist class with authority. An historical anthology with contributions from the five Nordic countries and an American editor used the phrase of Alexis de Tocqueville as a descriptive title for the egalitarian ideology underlying these societies: “A passion for equality”. Central for the Norwegians were support of social harmony, and compromises in situations of conflicts of interest (Graubard, 1986). The Norwegian contribution was written by the historian Hans Fredrik Dahl, and called “Those equal folk” (Dahl, 1986).

This very brief outline of Norwegian historiography provides a background for understanding egalitarianism. The tradition of writing history from the perspective of the nation has been particularly influential in Norway, often highlighting exceptionality. A belief in Norway as the land of self-owning farmers characterised by unique equality since medieval times has been perpetuated. There is, however, no clear statistical support for the widespread belief that Norway in the nineteenth century was more egalitarian than other European countries. Income taxation was non-existent or minimal; ship owners and other businessmen made fortunes, while the salaries and accumulated wealth of the embetsmenn were such that it also made them something of an economic elite. In fact, historical data on wealth and income inequality show that the Norwegian levels are far from exceptional (Aaberge, Atkinson, & Modalsli, 2016). At the same time hundreds of thousands emigrated to America because of the lack of opportunity in Norway. Except for Ireland, no other European country lost a larger portion of its population to overseas emigration. One hypothesis that has been posed by Jakobsen (2019) is that emigration would not have reached such levels if wealth had been more equally distributed.

In sum, one could say that the national narrative about Norwegian egalitarianism contains mythic elements, or at least not a detailed and accurate description of societal relations, but it is a highly effective and historically powerful narrative.

I will here mention two supplemental aspects of the development of history as a subject in Norway. The first aspect is an increasing sensitivity for questions of inequality. Ericsson, Fink and Myhre (2004, pp. 8–10) were the first to study the middle classes, and they wrote: “[Scandinavian] societies were distinctively coloured by their middle classes, and yet these groups represented a shadowy and almost anonymous presence in both contemporary and historical analysis”.[ii] Now, after their middle-class project, the conditions changed. Myhre (2004, p. 107) claimed that one reason for the absence of the middle class(es) in Norwegian historiography might be that up until the 20th century it was a small and rather unimportant group, and also that historiographical developments reflect contemporary society. Most attention was given to the working classes and the farmers, as well as the upper class. In the beginning of the 19th century, exporters of lumber, metal and fish were referred to as “lumber patricians”, “lumber nobility” or “Christiania nobles”, even though Norway did not have any formalised nobility. According to Myhre they were considered a cultural elite. When it comes to lifestyles however, Myhre (2004, p. 135) found that the middle-class lifestyle was “more or less an imitation of that of their social superiors”, but also that “take it to the extreme” and overdo the lifestyle “out of social insecurity” was common.

The second aspect is the shift in focus from Norway to a wide diversification of subjects with different methodological and theoretical approaches. The subject of history is considered to be less unified today than before. The new method for defining the discipline of history appears to be the method of elimination, that is to draw boundaries towards what cannot be considered history, rather than being on a quest for defining the absolute core of the subject (Halvorsen, 2016b).

2.4 Sociology – a sensitivity for inequality

There are few studies of when, how and why sociology emerged in Norway, but the narratives about the emergence often start with key figures. The key figures that are claimed to do sociology before sociology was formally institutionalised are Ludvig Holberg (1684–1754) and Eilert Sundt (1817–1875) (Engelstad, Grennes, Kalleberg, & Malnes, 2005). They were both initially theologians. They are reckoned as founding fathers of social sciences in general in Norway, but Sundt has been of greater importance for sociology’s self-understanding. Sundt was also a priest, and wrote studies based on ethnographic approaches in between the 1840s and the 1860s (Stenseth, 2000). He wrote studies about urban poverty, rural farming, and health among other things. His focus was on specific disadvantaged groups, and he divided the population into two groups: the propertied and the non-propertied. Sundt overlooked the middle classes just as the historians of his time did. After him, several decades passed before sociological studies were undertaken. In the 1950s, sociology began its formal disciplinary history in Norway, through an initiative by students in Oslo, surrounding Nils Christie (1928–2015) and at the Institute for Social Research. Similar to other European countries then, it is hard to find the origin of sociology in Norway, but the formal organisation of it begins after the second world war (Wagner, 2001). The first introductory book in sociology was written in 1964 by Vilhelm Aubert (1922–1988), and simply named Sosiologi [Sociology]. Sociology from the founding period in the 1950s and 1960s is called both the “golden age” and the period of “problem-oriented empiricism”. Central works are Ottar Brox’s study of Northern Norway, Sverre Lysgaard’s study of “The Workers’ Collective”, Thomas Mathiesen’s study of inmates and Harriet Holter’s study of women’s role conflicts in industry. The historian Fredrik W. Thue (2006) provides an extensive account of this period in his thesis, and what Holst (2006) has called the “critical-normative backsliding“ of the period. Golden age sociologists were influenced by empiricist philosophy (especially by Arne Næss), American surveyresearch, and structural functionalism (Mjøset 1991, p. 150), but most importantly they wrote about Norwegian matters, and became “the guilty conscience of the welfare state’. Central to this notion is, on one hand, the task of measuring the intentions of the welfare state to provide equal opportunities and fairer distribution, and on the other hand pointing out that the basis for the welfare state lies in a system based on inequality. As Mjøset (1991, p. 162) wrote: “[T]he sociologist [of this era] is a populist because his starting point is the community, and the welfare demands of the family”. However, the elites and the educated middle class were not studied in this period, but rather specific groups and institutions oriented towards integrating members into society.

Sociology has followed the tradition of historians in writing large-scale works about the Norwegian society, and one of those works is actually called exactly that, Det norske samfunn [The Norwegian Society]. The first edition was published in 1968, edited by Natalie Rogoff Ramsøy, who was educated at the University of Chicago, but at the time associate professor at the University of Oslo. The second edition, from 1975, was edited by Ramsøy and Mariken Vaa (also at UiO). It established that Norway has an egalitarian stratification pattern (Torgersen 1975, p. 524). A third edition was published in 1986, with Lars Alldén added to the editorial team, and after that the editor was changed completely. Ivar Frønes and Lise Kjølsrød, both sociologists at the University of Oslo took over, and have edited the 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th editions of the book, where the last edition had so many chapters that it was separated into three volumes. The book has often been read as a representative example of, and even “mirroring”, developments within Norwegian sociology (Aakvaag, 2011; Pedersen, 2015; Slagstad, 2016). When summarised, the story that this book series tell, is a story of ambitions of describing the totality of the Norwegian society, strongly influenced by functionalism, towards an increase in topics and a rejection of describing what holds the society together. There is no clear unity in theoretical inspiration, and maybe even a lack of theorising (Aakvaag, 2011). A trademark has been “a sensitivity for inequality”, which I think can be extended to describe the general trend within Norwegian sociology (Pedersen, 2015). However, the last edition received harsh criticism for excluding a chapter on class and inequality, and it has been claimed that the expansion of the project reflects the discipline’s lack of identity (Slagstad, 2016). Slagstad’s criticism begs the question: when sociology no longer defines itself with reference to inequality, what is it then?

Else Øyen’s introductory book from 1976 has a telling title: Sociology and Inequality. She states that there is no “official policy for the amount of equality – or inequality – there should be in the Norwegian society” (Øyen, 1992, p. 23). This underpins the sociological normative position of having the perspective of the disadvantaged. It also shows a strong connection to “official politics”. To a large degree this characterises the sociological ambition of research during these decades: inequality was on the agenda, to deal with these issues in a political manner.

The general depiction of the Norwegian society by the sociologists was in other words pointing out how the social democratic ideals of equality were not realised, or at least not as successful as sometimes described. Through telling an evolutionary story about the development of Norwegian society, these aspects were assumed to gain less attention than they deserved. One consequence was that the more “idealistic” sides of the culture of equality in Norway were studied by other than the sociologists, namely the anthropologists, especially Marianne Gullestad. In the 1970s, they started doing fieldwork in “their own societies”.

Gullestad (1984, 1991, 1992) has been of vital importance to the understanding of equality from a social scientific perspective. Her anthropological accounts of everyday life in Bergen have emphasised the layperson’s understanding of equality as sameness, in addition to highlighting the importance of equality as a value in Scandinavian countries. Gullestad (1992, p. 6) summarised the egalitarian ethos as under-communication of differences. She finds this in her material when she sees that the working-class mothers she studies do not protest, they rather “turn their backs on politics and bureaucracy by creating their own worlds and these worlds can be analysed as a more indirect resistance to “the system”. Another anthropologist that has been working on Norwegian society and the concept of egalitarianism, is Hallvard Vike (Bendixen, Bringslid, & Vike, 2018; Henningsen & Vike, 1999; Lien, Lidén, & Vike, 2001; Vike, 2018). He claimed that Norwegian political culture is characterised by a moral elite control, where the elites are sanctioned morally and thus not able to transcend cultural restrictions that are a part of Norwegian culture.

Also worth mentioning, is two Government initiated studies of power in Norwegian society, with sociologists in central roles, the “power investigations” (Götz, 2013). The first was led by Gudmund Hernes from 1972 to 1982, and the second by Fredrik Engelstad and colleagues from 1998 to 2003. Both had an ambition of describing power relations within Norwegian society, and thereby providing important information both for public discussion and political deliberation. The second investigation, Makt- og demokratiutredningen [The power and democracy investigation] had an explicit focus on the democratic (legitimate) exercise of power. The first is considered to be influenced by American political science and positivism, whereas the second had a broader methodological approach. The second investigation also had internal disagreements in the leadership group, where Hege Skeje dissented based on gender issues and methodological nationalism, and Siri Meyer dissented based on disagreements about the concept of power. Two social scientists and the sociologist (all of them men) formed the united conclusion: Øyvind Østerud, Per Selle and Fredrik Engelstad.

Up until today a research group has studied elites from a similar kind of perspective as the “power investigations”. They use the positionality method, by selecting people in important positions, instead of the reputation method or the decision method. Survey research seems to be the preferred method. The latest result from this strand of research is Trygve Gulbrandsen’s Elites in an Egalitarian Society (2019), which found that elites are well integrated in Norwegian society and strongly support the labour unions, and the anthology Eliter i endring [Changing elites] (Engelstad, Gulbrandsen, Midtbøen, & Teigen, 2022).

The study of inequality focusing on taste and lifestyle differences has been one in which sociologists have excelled. On the one side, we find studies of taste, aesthetics, and culture, and on the other side studies of inequality, hierarchies, class, and mechanisms of reproduction (Jonvik, 2018). Many studies have also analysed the connection between, how tastes, preferences, and cultural valuation are connected to and/or reflected in other social inequalities. A typical discussion here has been the question of whether the inequality levels in Norway have similarities with trends in other countries, or whether egalitarian aspects of the society make it less suitable for analysing with concepts that are derived from studies of other societies. In this latter vein, we find Arild Danielsen’s (1998) critique of the conceptual translation of cultural capital from French to Norwegian societal relations. In his view, the different modernisation processes of the two nations mean that the content of a concept will differ, especially that the status of continental high culture is very different in the two countries.